Exploring Racism with the CRC

Roxanne Felix-Mah and Kaitlin Lauridsen lead a conversation about racism with the Shift Lab

What do we think of when we hear terms like “white privilege” and “white fragility”? What is the difference between prejudice and bias? How does colonialism relate to power and how do both relate to whiteness? Well, our friends at the Centre for Race and Culture helped us find out some of these answers inside a Canadian context. And, to be frank, in a world where Donald Trump is the President-elect of the United States, that these are vital questions is a gross understatement.

As has been repeatedly evinced, a gi-normous part of the problem we collectively have with race today is wrapped up in how we talk about it. This is because we don’t know how to; I like to say there are no right ways to talk about race, only plenty of wrong ways. The US election brought a number of race-based terms to our public discourse—privilege, alt-right, white fragility, to name a few—but it is nigh impossible to agree on what any of those terms mean, their implications or redresses. Stripped of these things, for better or for worse, we end up having this discourse on Twitter. (Decidedly worse.)

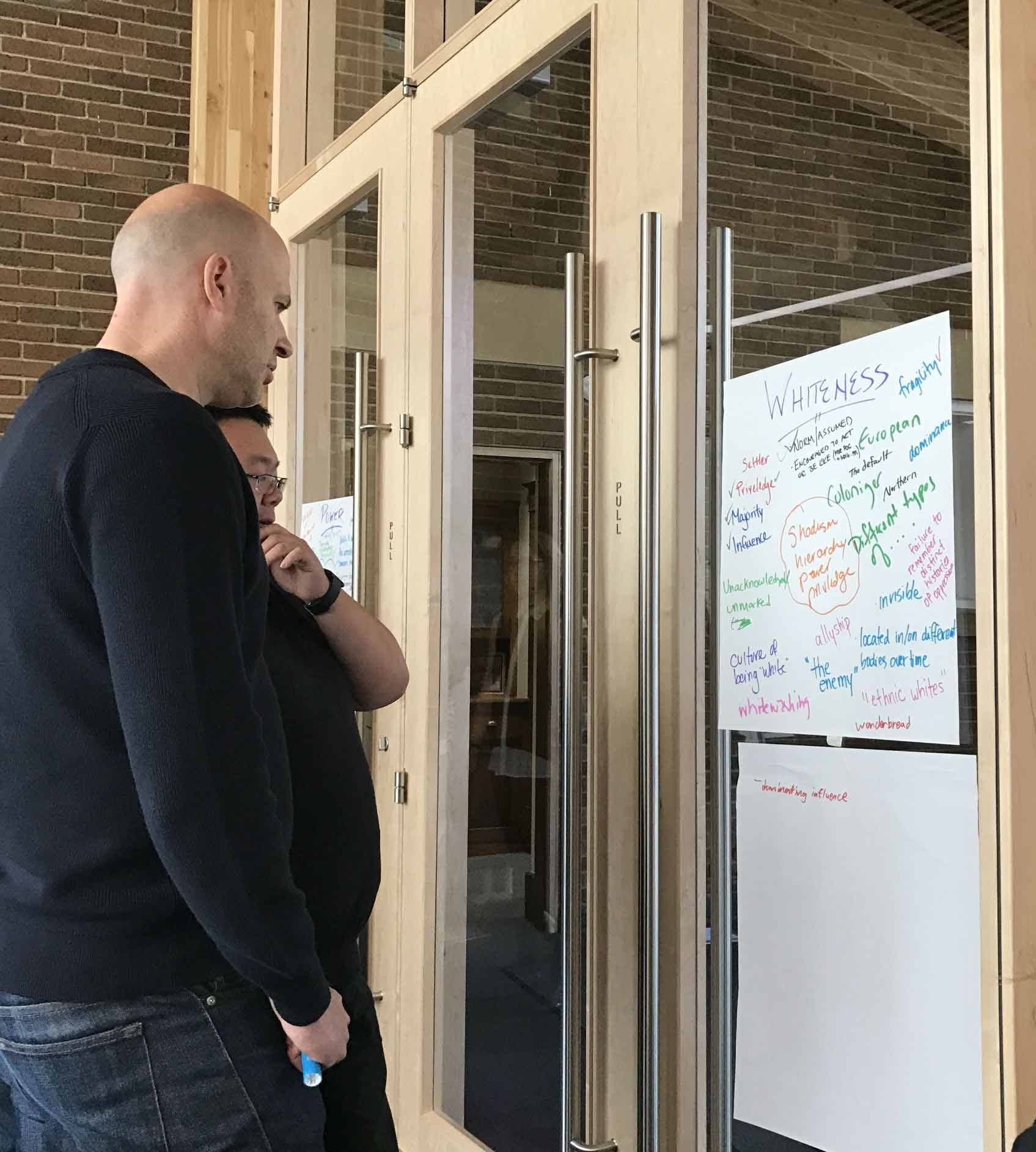

Pieter and Francisco defining whiteness. If they can do it, so can Twitter.

It is hardly a generalization to say that we don’t like to talk about race in Canada, and certainly not to the extent that our American cousins do. Mostly, these conversations have been taking place in minority-centric or niche-specific media like Canadaland. One notable mainstream exception is the Globe and Mail’s podcast Colour Code, led by Denise Balkisoon and Hanna Sung, which is trying to bring a conversation about race to a wider audience.

We can’t start talking about racism without the foundation of a shared understanding. The Centre for Race and Culture, a small, Edmonton-based non-profit consultancy, took us through a day-long series of exercises where we examined concepts like colonialism, prejudice, race, whiteness, discrimination, and other hugely-loaded terms.

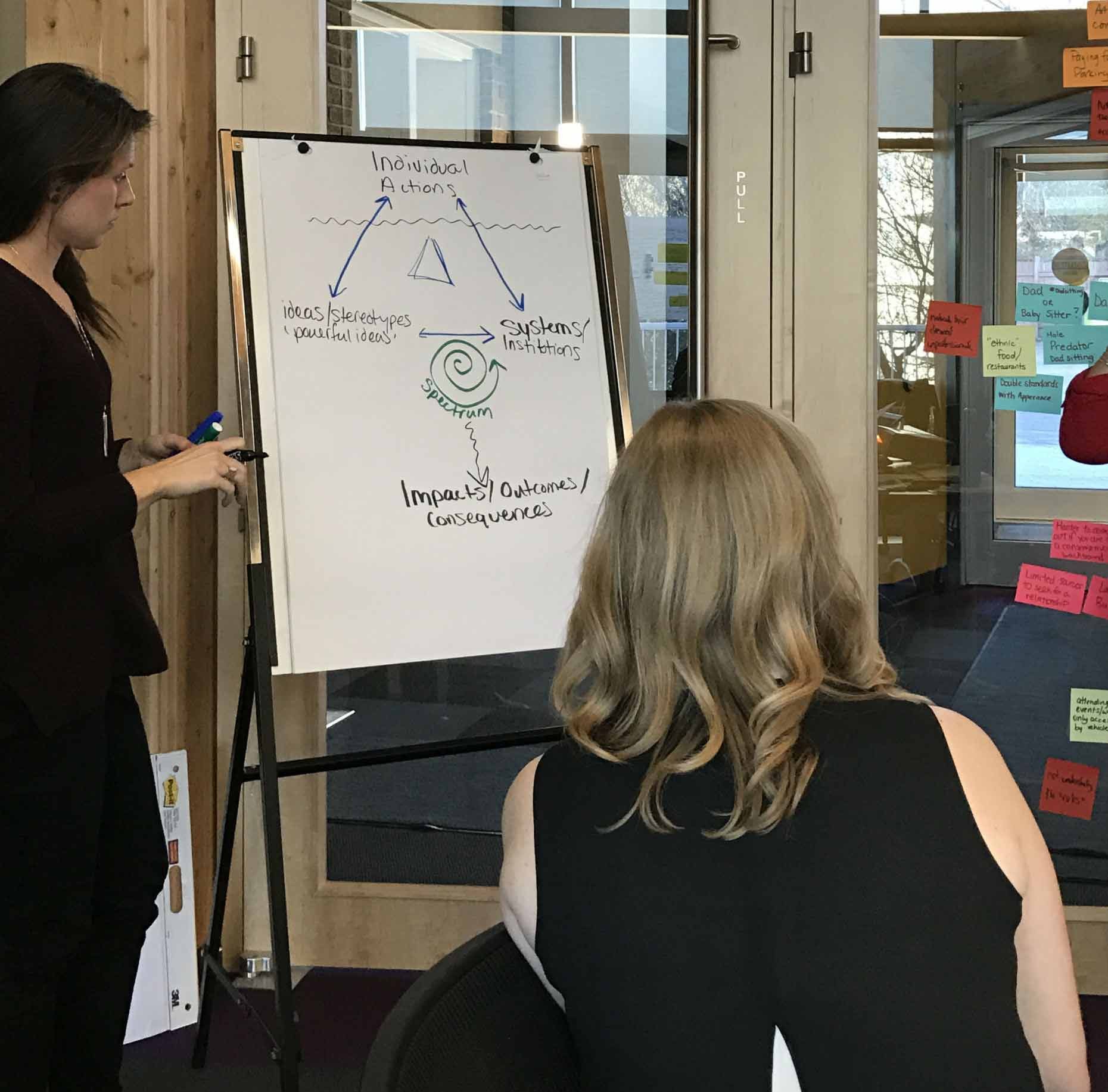

Kaitlin demonstrates the Triangle Tool for Oppression/Equity Analysis

If the ultimate root of racism is ignorance, then knowledge—specifically knowledge of our history—is the answer. Canadians pride themselves on having a less violent and cruel history as the United States and elsewhere, but even a cursory examination of history shows that we have our own shadows to contend with. The warts of Canadian history—such as the Indian Residential Schools, the Komagata Maru incident, internment camps (of Japanese but also our Austro-Hungarian and Ukrainian populations, who were also ‘othered’ during World War I) are starting to see the light of day. But we also looked at unsung heroes, like Viola Desmond, Canada’s Rosa Parks, and progressive policies such as the current federal government’s expressed desire to implement the recommendations of the landmark Truth & Reconciliation Commission.

Most of these incidents do pop up in our schools, Heritage Minutes, and even (soon) on our currency. But for all their implications, these events are not known nearly as much as they should be. Admittedly, the stewards and the core team are equally excited that the most ambitious incorporation of aboriginal-related school curricula anywhere in Canada is happening here.

Of course, the discourse around these topics is highly charged, deeply personal, overtly political and enormously contentious. At the same time, it feels like race relations are at a crisis point in Canada, the United States, Europe, and elsewhere. If we are going to start talking about race, here’s hoping we are ready to have those conversations.